|

| The 4Gs: George, George, George & George |

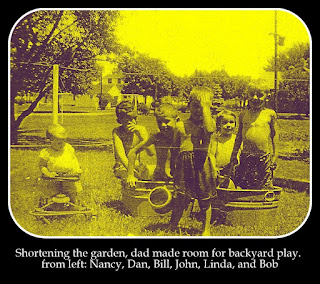

I’m a grandmother now, the ninth of my twelve siblings to add

to the next generation of Kerbers, even though my grandson’s surname is

Schmitmeyer. But his given name is George, a Kerber name, making him one of

four living Georges in the family. There is my younger brother George, who was named

for our father, and two nephews, the sons of brothers George and John, and my

grandson, George Simon Schmitmeyer, who is three months old.

I was happy about his given name, of course, and when my grandson

is a little older, I’ll want him to know about the extended family into which

he was born. Knowing familial connections helps us feel grounded; they make us

feel part of something greater than ourselves.

|

| Our father, the original George |

A way of nurturing family connections is through sharing

stories, something our family has done in various ways through the years. Most

recently it has been with this blog, but there have been other ways, too.

After Dad died and Mother decided to move out of 828 Spruce Street—almost forty

years after she and my father moved in. Our family had a house-leaving party to

divvy up the family artifacts, but also to say good-bye to the place we once

called home. The get-together was held Thanksgiving weekend in 1988, and to

commemorate the occasion, Mother asked each of us to write down our thoughts about

828, which we shared at the party. As

you can imagine, there were lots of tears and laughter as we read what

we’d written.

|

| Thanksgiving 1988, toasting good-bye to 828 Spruce Street |

There have been other ways of telling family stories through

the years. As we kids grew up and moved away (we now live in six different states),

we circulated a family newsletter for a couple of years. Called the Zweibach Times, it contained family

updates and was named for the after-school snack Mom made from stale bread. (Zweibach is German for twice-baked, and she’d

heat the bread pieces in a low oven for a long time and serve them warm with

butter.)

It was Mom who, by example, encouraged our family’s writing.

When each of her grandchildren turned sixteen, she wrote them a story about her

life as the oldest of eight children growing up during the Depression. She told

of the houses she lived in, the games she played, the horse-drawn buggy she rode

to church in, even of living with my two oldest brothers in San Diego where Dad

was stationed during World War II. Like the Zweibach

Times, her birthday letters serve as a link to our family’s history.

|

| Liwwät tombstone at St. John's |

But the idea of recording life’s daily events can be traced

deep within Mother’s heritage; her great, great grandmother was Liwwät Böke, a

pioneer woman whose writings and drawings were published by the Minster, Ohio,

Historical Society in 1987. The book, Liwwät

Böke, 1807-1882, Pioneer, is a detailed account of everyday farm life in

the mid 1800s. For many years, Liwwät wrote and drew pictures on the sheaves of

paper she brought with her from Germany. In her writings, she tells of her

passage to America and the challenges she and her husband Natz faced farming

the dark wooded land near St. John’s, then a fledgling community near Minster.

She also wrote about of the loneliness frontier women experienced as they

settled into life far from their extended families.

Liwwät also tells why she spent so much time recording the

details of her family’s life, despite the many struggles of her pioneer life: “Perhaps

twenty, thirty, or ninety years, my children’s children will come to read my

writings and to look at my various drawings and they will better understand who they are, and will know that Natz and I

were really living persons.”

|

| From Liwwät's book: The Boeke cabin a year after coming to St. John's |

Maybe one day my grandson George Simon, born more than two

centuries after his great great great great great Grandmother Liwwät, will know

our family’s stories, and that the people who grew up at 828 were once “really living

persons.” And maybe by knowing this, he will have a greater sense of who he is.

—Linda